by James Hansen

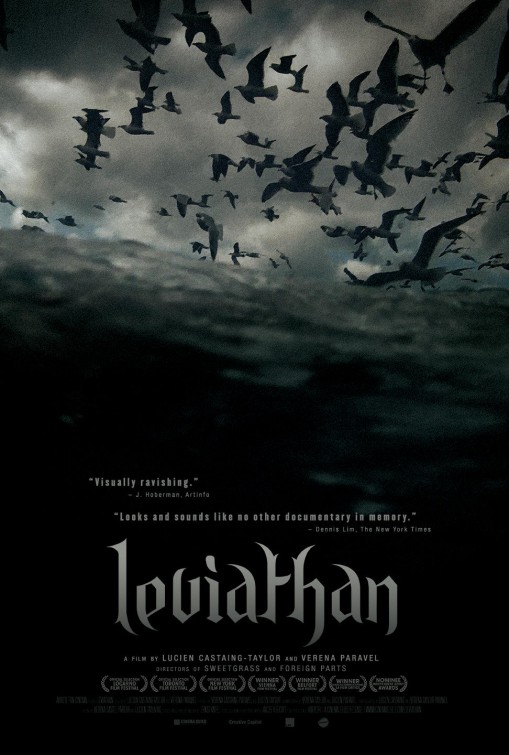

It is practically useless to describe Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Verena Paravel’s experiential documentary Leviathan, surely one of the most enthralling and terrifying films of the year. Ostensibly about the commercial fishing industry, the directors utilize mini-waterproof cameras to gain access to various locations and points of view on board a fishing vessel. While there are certain precedents for this kind of “observational” filmmaking, Leviathan is truly something no one has seen or heard before.

The film doesn’t merely function at the level of “How did they do that?” but extends further into “What, how, and where in the hell am I looking?” The opening sequence begins with a soft bounding light, tilted slightly sideways with creaky sounds and rushing waters barely visible amidst the great darkness. Castaing-Taylor and Paravel’s editing is so sharp, the sequence seems to extend endlessly, the flow of the waters matching the smashing, whipping sounds of the ocean and the fishing vessel even as human figures arise from the darkness. The shot seems to go on forever, the energy rapidly increasing. One would think it impossible to sustain this wild energy throughout the running time, but through the expert sound editing and avant-garde editing techniques, constantly cutting and either sound or motion, Leviathan maintains its wild, exhausting, haunting mood for its entirety.

Of course, this says nothing of the indescribable, topsy-turvy cinematography, which, as Blake Williams has already noted, “seems to be first and foremost an attempt at recalibrating viewers’ sense of gravity.” Even the most stable shots in Leviathan find an odd orientation or evoke bizarre feelings. More often than not, the camera bounds up and down, spins left or right, floats above the bodies of death fish, waves with the vessel in and out of the choppy ocean waters, barely peering above the surface to find various fragments of lights or blindingly white birds cast against the pitch black background of the night sky. Another scene – an act break of sorts – finds a bird trapped in the boat before finally plummeting off the side of the boat.

Achingly beautiful, Leviathan illustrates a matter-of-factness that transforms the film into a form of admiration and, indeed, horror. The brutal, repetitive, mechanistic (but not entirely mechanical) labour take its toll on the human body of the workers, as well as the eyes of the viewer. After nearly 90 minutes of twisting and turning my own head to try and locate myself or the image within some knowable space, it becomes clear that Leviathan locates itself in an other space – in the world of something unknowable that can nevertheless be witnessed.

No comments:

Post a Comment