By Brandon Colvin

When it comes to Watchmen, it is impossible for me to be an unbiased or even level-headed reviewer. I am, unabashedly, a full-fledged “fanboy” regarding Alan Moore’s 1986 graphic novel. Having read the book over and over, each time feeling more and more slobberknocked by its complex, interlocking structure and carefully crafted plotlines involving the deepest and darkest philosophical and moral conundrums (pretentious but true), I have concluded that Watchmen, the graphic novel, is my favorite non-film narrative . . . ever. (Cue the sneers toward my hyperbole.) As a cinephile, however, much of my appreciation of Watchmen, the graphic novel, comes from my observance of its highly cinematic qualities: movement, angles, juxtaposition, rhythm, visual rhyme, lighting, and framing (not to mention the various cinematic influences on the book’s storytelling from film noir to Dr. Strangelove (1964) to Taxi Driver (1976)). The whole graphic novel is perhaps the closest thing to a movie-on-a-page I have ever experienced, existing in a creative sphere that is just as informed by cinema (if not more) than it is comic books – paradise for a nerd like me who wishes he could sit around and read movies when he isn’t watching them.

Herein lies the predicament of my writing about the cinematic adaptation of Watchmen – I’ve been adapting it for the screen in my head from the very first time I read it. The book was always waiting to be a movie; it only made sense. This, of course, is not true for everyone (as I have been repeatedly informed by the film’s detractors). Therefore, I come to this review as a “fanboy”/film critic in a mild identity crisis. How can I write about this film judging it solely on its cinematic merits when I judged the beloved inked source material, in many ways, based on its cinematic merits? Should I write as if I were not familiar with the graphic novel, like many viewers and reviewers, or should I write as the avid fan that I am? If Watchmen has always existed for me in at least a proto-cinematic realm, how can I express the inevitability and desirability for a filmic adaptation to someone for whom this is not the case? How do I concretely differentiate between a cinematic graphic-novel and a comic-book-like movie?

Okay, okay. This is getting neurotic. You get my point. Extracting my personal investment in Watchmen from my critical perspective is as impossible as it is pointless. I could argue about the validity of its themes, the depth of its characterization, the myriad contradictory conclusions and implications found within its story – all of the elements that can be found in the source material that mean so much to me; however, what I want to attempt to discuss here are the differences between the print and screen versions of Watchmen: what makes the movie more or less successful than the graphic novel and what, if anything, gives it a creative life of its own.

I would insert a plot summary here, but honestly, it would be futile. Summarizing the plot would take up as much space as this entire review . . . it’s pretty intricate. Try Wikipedia – the article on Watchmen is very extensive and thorough.

I’ll begin my assessment of the actual film by responding to a widely-held criticism of the movie – namely, that the Watchmen film is too close of an adaptation of the graphic novel, relinquishing storytelling power via cinematic language in favor of faithfulness to the book’s panel designs and framing. To this, I say, “bollocks.” Watchmen’s (the film) visual storytelling is one of progressive tableau and densely packed framing – certainly in keeping with the methods of the graphic novel, but doing so in a way that is also undeniably cinematic. Why is there a difference in value judgment when describing a film as being “painterly” and describing a film as being like a graphic novel – essentially multiple paintings in juxtaposition? Why is it unacceptable for a film to use the tableau style of comic-book panels to tell a story when those very comic-book panels are, in fact, derivative of previously established cinematic styles? The line seems much too blurry in this instance for me to distinguish what about Watchmen is strictly graphic novel-influenced and what about it is dependent upon filmic traditions. Ultimately, I ask, why does it matter? The techniques of Watchmen undoubtedly add up to a viable cinematic style; I’d say Wes Anderson’s films are just as dependent on artificial, dense framings with relatively little camera movement, much slow motion, and very pictorially expressionistic designs. If The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) were a graphic novel first, would it be undergoing the same criticisms as Watchmen? I think not. Since when is making a formally analogous adaptation a major sin, especially when, in my opinion, it works?

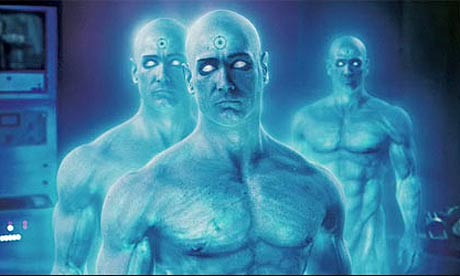

Aside from quarrels with the validity of director Zack Snyder’s quite meticulous adaptation, many complaints regarding the film seem directed at the liberties taken by David Hayter and Alex Tse in their script, which certainly strays from the content of the graphic novel while consistently preserving its brooding, ironic spirit. In order to avoid spoilers for those readers still waiting to see the film, I’ll merely say that both the beginning and end of the film are altered in ways that are very noticeable – rearranged order/continuity and even entirely new plot elements – but, these changes, as well as those throughout the film, are often made in the name of elegance, simplifying some of the more complex and inaccessible aspects of the Watchmen to the point that a theatrical, commercially viable film could be produced. Most “fanboys” seem to have a problem with this; I don’t. It is semi-miraculous that this film even exists and, honestly, I expected it to be a lot worse. Hayter and Tse’s changes introduce new, very interesting dynamics to the plot – including further probing Dr. Manhattan’s (Billy Crudup) potentially cataclysmic role in the alternate reality – and, in many cases, play up the book’s humor. Although some key facets of the graphic novel’s thematic relevance are lost or shuffled, new elements are gained that distinguish the film from its source material; case in point: the soundtrack.

For most fans of the graphic novel I’ve spoken to, the film’s use of chuckle-inducing tunes at the most unusual moments has been off-putting. To me, it reveals that Snyder, Hayter, Tse and the rest of the filmmakers understand the big joke, the ultimate cosmic irony of the whole narrative – the one The Comedian (Jeffrey Dean Morgan) is always talking about and the one that Rorschach (Jackie Earle Haley) claims to understand – deciding to infuse its hilarity into numerous moments throughout the film, the most discussed of which is certainly the now-infamous “Hallelujah” sex scene between Silk Spectre II (Malin Akerman) and Nite Owl II (Patrick Wilson), aboard the latter’s gorgeously rendered flying owl ship, Archie.

A classic case of Watchmen wit, the scene mounts a comical critique of the sexual limitations of its deeply flawed characters, comments on the fetishistic qualities of playing dress-up do-gooder, and implicitly lampoons the super-serious model of superhero stories epitomized by last year’s The Dark Knight – all of which is highlighted by altering/adding to the contents of the graphic novel through the song. In the book, the sex scene is treated quite seriously and the characters’ references to the way wearing their costumes and saving civilians from a fire cures Nite Owl II of his previous impotence is rather straightforward. In the film, the humor of Nite Owl II’s bedroom issues and his dependency on role-playing to get his jollies is amplified by the addition of Leonard Cohen’s song, which coats the scene in a too-serious, too-romantic, trying-too-hard sheen that is as obviously artificial as it is intentionally sarcastic. Using the musical elements unique to the film, Watchmen extracts levels of meaning and presents tonal angles that are somewhat buried in the graphic novel, bringing to light the well-sewn seeds of comedy that line the narrative’s ostensible gravity, while also providing a counterpoint to the total Seriousness that seems to be expected of all comic-book movies in the wake of Christopher Nolan’s somber blockbuster. Which is not to say that Watchmen isn’t a morose film, but at least it seems to understand the value of levity and acknowledges the inherent absurdity of its own fantastical apocalyptic scenario.

Obviously, I’m a bit long-winded regarding this film, which is a fault of my own; Watchmen rattles my brain to the point of discombobulation. To be short, the film is worth seeing. It is worth seeing multiple times. It is different enough from the graphic novel to earn its status as a strong, individual work on its own. If you don’t like the book, however, you probably won’t like the movie. If you haven’t read the book, you should before watching the movie. (Whether that is a flaw in the movie or not, I can’t say. Topping the book is a relatively impossible feat.) The film is by no means a masterpiece, but it is nonetheless impressive in its ambition and execution. There were moments in which I was amazed and others in which I was befuddled, but, as a passionate supporter of the book, I must say I was not disappointed.

Continue reading...

Showing posts with label adaptation. Show all posts

Showing posts with label adaptation. Show all posts

Tuesday, March 17, 2009

The Curious Case of the "Fanboy"/Critic

Labels:

adaptation,

fanboy,

Graphic Novels,

music,

Watchmen

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)