***Note: This sentence has lead to some confusion and was poorly worded. Polley speaks with her actual siblings throughout the interview process. In the faux-archival footage, however, they are played by other figures (as mentioned in the previous sentences). Here, I am trying to point to this productive slippage between fact/fiction that resonates throughout the film. Actors do not play the siblings in the interviews, although I would suggest the fact that the documentation becomes skewed suggests a neat, stage-like quality to the interviews themselves in which truth/falsity can still be raised. [Thanks to Peter Labuza, Jim Gabriel, and Corey Atad for raising these points.]

Monday, July 15, 2013

A Tidy Mosaic: Stories We Tell (Sarah Polley)

***Note: This sentence has lead to some confusion and was poorly worded. Polley speaks with her actual siblings throughout the interview process. In the faux-archival footage, however, they are played by other figures (as mentioned in the previous sentences). Here, I am trying to point to this productive slippage between fact/fiction that resonates throughout the film. Actors do not play the siblings in the interviews, although I would suggest the fact that the documentation becomes skewed suggests a neat, stage-like quality to the interviews themselves in which truth/falsity can still be raised. [Thanks to Peter Labuza, Jim Gabriel, and Corey Atad for raising these points.]

Saturday, March 23, 2013

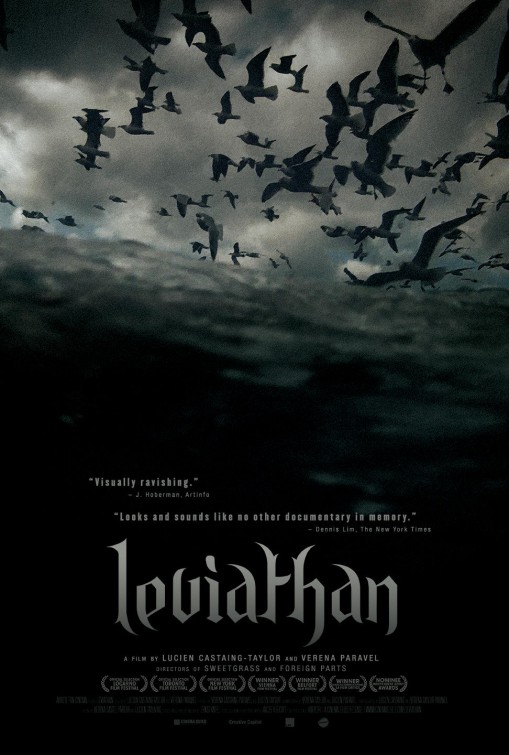

Leviathan (Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Verena Paravel)

by James Hansen

Monday, August 22, 2011

Morris Makes a Tabloid, For Better and Worse

This summary is not available. Please click here to view the post. Continue reading...

Monday, April 20, 2009

Migrating Forms 2009: "DDR/DDR" (Amie Siegel)

by James Hansen

Eventual winner of the Best Long Form (i.e. Best Feature) Award at the inaugural Migrating Forms Festival, Amie Siegel’s DDR/DDR was a fitting winner as it seemed to encompass many of the festival’s obsessions (religion, national identity, “new media”’s relationship with cinema), while it also offers formal challenges to the documentary form sure to puzzle as many viewers as it enthralls.

DDR/DDR, previously shown in New York at the 2008 Whitney Biennial, takes as its main focus the failed East German state, most namely the Stasi organization. Excavating Stasi archives, Siegel uncovers a strange past and examines the modern relationship that former citizens have with their East German heritage. In both instances, the lines, walls, and barriers between the state and its citizens are constantly challenged, as, the work argues, the lines between victim and perpetrator are never clear.

DDR/DDR traces these problems by tracking the discursive nature of media technology – both through East Germany’s obsession with the Western genre (leading to odd works such as The Sons of Great Bear (1966) which DDR/DDR examines in depth) and Siegel’s own attempts to correctly convert the video’s own message from one spatio-temporal period to the next. The centerpiece of DDR/DRR is a long set of interviews with former East Germans who have created their own Indian commune. Siegel works with these “Indian Hobbyists” to explore their identification with, and removal from, the East German state. Here, the “hobbyists” can perpetrate, as the video argues, their continuing role as a victim in a German society that split half its existence.

The camerawork of the interviews, almost always medium or long shots, keeps DDR/DDR at an appropriate distance from the people and their own cultural identities in order for Sigel’s meta moderating commentary to play with its own “free associative” structure and ultimately allow it to conceptually discover its own identity. This, of course, all plays out in a striking manner. The balance between fact and fiction is iterated formally, similar in many ways to more recent work by Jia Zhang Ke, with a mix of staged and scripted interviews, as well as Siegel’s addition of an overtly reflexive questioning of the work’s processes, functions, and techniques.

With its own focus on the migration of culture, identity, and history, DDR/DDR positions itself in many places at once, while highlighting the fine line between the conclusions it draws and previously established modes of historical identification. A true summation of a Migrating Form, DDR/DDR is a uniquely meditative work with no specific identity as a documentary, fiction, or gallery piece – a perfectly fitting, successful assemblage that reasserts its own communicative strategies and structural challenges. Like its title, DDR/DDR feeds back into itself in nearly every manner, while questioning each movement along the way.

Continue reading...

Saturday, March 14, 2009

DVD of the Week: "Tongues Untied" (Marlon Riggs, 1989)

Sorry to everyone for this being a day late. Reviews of Miss March, Last House on the Left, Watchmen, and Hunger are in the works.

by Chuck Williamson

Tongues Untied, the 1989 video collaboration between media artist/queer activist Marlon Riggs and poet/essayist Essex Hemphill, has been burdened for too long by its legacy as a polemical culture war product. When it was first broadcast on public television, the documentary became the target of evangelical moralists and right-wing politicians—particularly Pat Buchanan, who used footage from the video in a presidential campaign ad accusing Bush of funding “pornographic art.” Thus, some might assume that Tongues Untied can only be appreciated as a timely polemic and historical footnote. However, the video defies such criticisms, as it represents both a moving and incisive mediation on the experiences of black gay men and a radical reinvention of the documentary form.

more after the break

As Riggs has stated, “Tongues Untied tries to undo the legacy of silence about Black Gay life.” Foregoing any traditional documentary approach, the video opts for a more experimental method. Blending spoken-word poetry, confessional interviews, and queer performance, Tongues Untied constructs its counter-discourses in response to the reductive, prejudiced view of black gay men, who are doubly-Othered and marginalized within both black and white culture. Through footage of dive bars, voguing balls, snap! performances, pride rallies, and on-the-street interviews, the video documents the cultural happenings of the black gay scene of the late eighties. But the video ultimately moves away from the limiting confines of an objective, journalistic discourse; instead, it fuses fact with fiction, personal testimonial with poetic recitation, on-the-street verite footage with experimental montage. Tongues Untied alternates between interviewed confessionals and prosaic poetry readings, documentary footage and staged homoerotic spectacle. These discursive strategies make the video’s explorations political and personal, thus adding to its urgency and poignancy. In its most powerful sequence, Marlon Riggs delivers a monologue that mixes poetic mediation with pained confession, as he speaks on the intersections of homophobia and racism, and the prejudices that exist within both black and white society. “Silence is my sword,” he says. “It cuts both ways—silence is the deadliest weapon.”

But Riggs’ voice is just one of many. Through the collaging of sound and image, spoken word and visual antecedent, the film transforms silence into a cacophonous roar—and it is a roar that includes many voices. In Tongues Untied, the experiences of black gay men cannot be viewed as singular or monologic, and the video demonstrates this by stitching together its various discourses into a polyphonic tangle that gives the viewer access to a broad spectrum of emotions and experiences.

Out-of-print for over a decade, Tongues Untied has finally been released on DVD by Frameline Pictures.

Continue reading...

Wednesday, August 13, 2008

DVD of the Week: "Symbiopsychotaxiplasm" (William Greaves, 1968/2005)

This week, Tropic Thunder will remind everyone how much fun watching movies about making movies (or rather a cast thinking they are making a movie) is. As disparate as these titles seem, the DVD pick for this week, William Greaves’s groundbreaking documentary Symbiopsychotaxiplasm, will be an interesting film to see immediately before or after you see Tropic Thunder. Leaving a crew in Central Park to discover for themselves what kind of movie they are making, Greaves incites the situation in Symbiopsychotaxiplasm which becomes an insightful look into the creation of a film. While Tropic Thunder seeks to satirize movies and the reasoning for their existence, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm questions itself as it unfolds and, though it is not a comedic satire, searches for something amidst the chaos and disorder of filmmaking. I haven’t seen Tropic Thunder yet, so this DVD pick is more of a hypothesis for what could be an enlightening pairing. If anyone else accepts this viewing challenge, I am sure the two films, at the very least, will CREATE something, in conjunction with one another, to discuss.

Note: On the Criterion DVD, both the original film, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (which the post refers to), and the sequel, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take 2 1/2, are available. If you only watch one you should watch Take One, but both versions are worth viewing if you have the time.

-James Hansen

Continue reading...

Monday, November 12, 2007

Diving Into Hot Water

A young black woman lies wincing on an inclined metal table. A tool that looks like a vacuum appendage or a dentist’s instrument is inserted into her pried open vagina. Liquid material is sucked up through the tool and down a hose, finding its resting place in what appears to be a coffee pot. A doctor dumps the contents of the coffee pot-like container into a metal tray and begins sorting amongst the bloody parts. He finds legs, hands, an ear, and a misshapen head complete with two fishy looking eyes. It was a baby. Or was it a fetus? Does it matter? Was it a human? Did it think? Did it feel pain? Does it have rights? Did the young black woman defy a vengeful God? These are the impossible questions asked in Tony Kaye’s brutal and unflinching “Lake of Fire”, the director’s long-awaited follow up to 1998’s “American History X.”

Produced over a span of 17 years out of Kaye’s own pocket, “Lake of Fire” is a documentary that displays in stark black and white perhaps the grayest issue in the moral spectrum. From start to finish of its 152 minutes, “Lake of Fire” is incredibly stimulating, dynamic and, most importantly, thorough. Perhaps no aspect of the abortion debate is left untouched. The documentary oscillates between interviews with pro-choice intellectuals like Noam Chomsky and Alan Dershowitz to footage of conservative pro-life extremists, including convicted murderers and abortion clinic terrorists, such as Catholic fundamentalist John Salvi and former Presbyterian minister and Army of God member Paul Hill. From the gut wrenching footage of abortions being performed to the mind numbing photographs of murdered abortionists lying in pools of blood, “Lake of Fire” presents a disturbing face-to-face encounter with the true depth of the abortion issue.

One of the more interesting arguments in the film comes from Alan Dershowitz’s close friend, writer Nat Hentoff. A fervent pro-lifer, yet a member of the ACLU and a staunch liberal, Hentoff came out as an opponent of abortion in the 1980s and was alienated from his fellow writers at The Village Voice. An atheist, Hentoff argues that abortion violates the civil rights of the child, which he describes as human, since once the zygote is formed the single celled organism is on an undeniable path toward becoming a “human.” Hentoff believes that since this being is in process to becoming a human, it should be given the same rights that its eventual teleology would allow it: the right to life as granted by the Constitution. His argument is intriguing and serves as one of the lone voices on the left against abortion. It’s especially resonant considering Alan Dershowitz’s claim that when he saw his own child on a sonogram he realized that it was a human, a living person. Dershowitz clarifies his statement, however, pointing out that his defining of his own child as a person was subjective and that for someone else, this classification may be completely different, and that the state has no right to legally enforce an opinion on a certainly arguable point.

Another beautifully crafted sequence details the path taken by Norma McCorvey, also known as Roe from Roe v. Wade. McCorvey, after a long period of depression and experimentation with drugs, turned to the evangelist anti-abortion group Operation Save America, where she continues to work under the tutelage of activist Flip Benham, who baptized her in his backyard on national television in 1995. McCorvey’s sequence illustrates an irrational, but completely understandable stance on abortion, one that is informed by a new hope in life that she attributes to God and the purity she sees shining through two young girls she became acquainted with at the Operation Save America ministry. Her transformation is seemingly miraculous and is treated sincerely and without condescension by Kaye.

Editing defines a documentary more so than a fiction film and Peter Goddard’s editing throughout “Lake of Fire” is absolutely jaw dropping. Goddard, no doubt in cooperation with Kaye’s overseeing vision, manages to transform a sprawling, tangent-ridden, back and forth issue into a cohesive visual research project illuminating each argument by contrasting it with others and placing it in new contexts. The high level of the philosophical, theological, political, and sociological discourse in the film validates the incessantly shocking aspects of the film by rooting them within an academic setting that verifies their necessity. Grisly scenes that could make even Cormac McCarthy blush are portrayed with subtle sympathy and humanism, circumventing the easy path of detachment that could’ve wrecked their presentation.

Almost as impressive as the tour-de-force editing is Kaye’s unfailing success when it comes to choosing iconic, haunting images. One scene involving a group of anti-abortion activists hammering crosses into a knoll in front of the Washington Monument is impressive in its ritualism, sticking in the mind like scenes from some of Ingmar Bergman’s most devastating works. Another iconic scene depicts a liberal man’s reactions to an anti-abortion protester’s statement that everyone who says “Goddamn” should be executed, as well as all homosexuals, fornicators, and blasphemers. The stunned man’s face hangs in disbelief, a symbol for universal liberal astonishment at such oppressive authoritarian mentalities.

Most importantly, “Lake of Fire” leaves no audience member untouched or unchallenged. When leaving the theater, viewers will undoubtedly be digesting a week’s worth of intellectual, ethical, and spiritual questions that will swish and throb in heads like moral migraines, begging to be nourished by serious thought. Even if Kaye never makes another documentary, his legacy as a great documentarian will be secured by the brilliance, originality, and sheer visceral power of “Lake of Fire.”

by Brandon Colvin

Continue reading...