by James Hansen

Simon West’s The Mechanic, a new version of the 1972 Charles Bronson film by the same name, starts as an existential character study, morphs half way through into a hitman apprenticeship story with no real purpose, and ends as a bizarrely off-putting, conspiracy-laden, action-espionage thriller. Without any connective tissue between these shifts, not to mention an unfortunate atonality and lack of conviction throughout, The Mechanic fails to succeed in any of its three mutated forms and piles up into a garbage heap.

Arthur Bishop (the always serviceable Jason Statham) is a “mechanic” – a hitman – for an international organization. He is successful and trusted because he follows orders and cleanly carries out his missions. The first 40-minutes or so of The Mechanic follow Arthur as he ponders his life of violence. A sweeping shot of Statham sitting in the dark here, a reverse version of the same shot there – existential crisis! After he is assigned a hit on his longtime friend, Arthur (for some reason) befriends Steve (Ben Foster), the son of the man he just killed. Steve, unaware it is Arthur who killed his father, lashes out after his father’s death at random car jackers. Finally, Arthur takes him under his wing and trains him to become a mechanic.

That getting through this basic premise takes nearly half of the 90-minute running time is the first (all too long) indication of adaptation trouble for Mr. West and screenwriters Lewis John Carlino and Richard Wenk; they have tried their hand at mimicking the atmospheric, silent opening of Jean Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (a hold over homage from the 1972 version, which apparently spends it first 16 minutes in silence as Bronson prepares his first job) – a difficult task, to say the least, and one that The Mechanic misses by a mile. Showing neither the restraint nor half the intellectual intensity of Melville’s classic, The Mechanic’s first half is both tedious and tepid.

In the second half, once Steve’s apprenticeship begins, The Mechanic becomes a different movie, but unfortunately still a bad one. Ignoring the potentially interesting relational dynamics between Arthur and Steve, The Mechanic turns into a hitman training video, except without any consequence. The sideshow of disparate missions (kill a Colombian, kill your backstabbing friend, kill a 6’7’ “mechanic” who loves chihuahuas and young boys, kill an obese preacher who think he is the Messiah, etc.) occurs without a semblance of context, randomly moving from one hit to the next without a framework for any kind of narrative urgency.

When Arthur sends Steve on his first solo job to hit the 6’7 “mechanic,” he warns Steve to keep it clean, do it in a bar, and don’t take on this guy. Of course, Steve doesn’t follow the directions, gets his ass kicked, and does the job as messily as possible, all to which Arthur merely chides, “I told you to keep it clean.” And, in the next scene, out of sight, out of mind. Here, The Mechanic reveals its pornographic action construction – rather than being strung together for sexual arousal, it gets off on action sequences functioning purely to fetishize violence and first-person shooter fantasies.

Needless to say, this makes the last-gasp injections of a double-conspiracy twist and a nonsensical coda (all on top of previously non-existent narratives) all the more hysterical. Statham is a strong action star, and Ben Foster’s feisty underling provides a good counterpoint to his stoic ferocity, but The Mechanic proves unwilling (or unable) to cohere enough on any level and properly utilize Statham’s badass persona (as was done in The Transporter series, Death Race, Crank 2 High Voltage, etc.) Rather, it sets a number of disassembled pieces beside each other and never figures out how to put them together.

Continue reading...

Friday, January 28, 2011

Back to the Junkyard

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

I Wanna Be Your Lover

by James Hansen

In what is sure to come as a surprise to entertainment prognosticators damning Natalie Portman’s Oscar hopes for making her post-Academy Award win “shit movie” before she even wins the award, Portman’s “shit movie” – Ivan Reitman’s No Strings Attached (and, incidentally, executive produced by Portman) – is far from an awards kiss of death (if you believe in such things) and actually shows more nuance than most mainstream romantic comedies, not to mention “awards movies” which seem more and more willing to abandon any subtlety in favor of bludgeoning audiences with their awardyness.

While not as radical as James L. Brooks’ How Do You Know?, the widely reviled film which found an equally ardent cadre of supporters (#TeamHowDoYouKnow?!), No Strings Attached literally passes over the typically conservative romcom formulas – the film opens with a seemingly sloppy sequence of flashbacks which hopscotch over classic romcom scenarios (questions of teenage virginity at summer camp, slutting it up in college frat houses) – and reverses them. Sex, here, is not an end goal where the triumphant white male claims his prize and high-fives his buddies. Rather, in No Strings Attached, sex is a given component of a relationship, a starting point from which issues of self inevitably arise for both persons involved. It isn’t really a question of “Can sex friends stay best friends?,” but when, why, and how silly pleasure transforms into more complex companionship. Oh yeah, it's also funny.

The aforementioned romcom scenarios revolve around Emma (Natalie Portman) and Adam (Ashton Kutcher), two sensitive, loner kids at camp who go different directions (he, a frat life at Michigan, she, working to become a doctor at MIT), before ending up in the same place (Los Angeles) where things come full circle. A night of binge drinking with his pals, Wallace (Ludacris!) and Eli (Jake Johnson), ends with Adam waking up in an unfamiliar apartment and re-living the classic college situation, Dude, What’d I Put My Dick In? Luckily, Emma’s doctor roomates, Patrice (the always exciting Greta Gerwig) and Shira (Mindy Kaling), resisted the swoons of a naked, depressed Adam. So, too, did Emma, at least the night before, but a passing glance here, a naked guy there, and their multiple almost-happened moments finally happens. No big deal – some afternoon sex, Emma’s off to work, and Adam heads home.

Naturally, this is just the beginning (else we wouldn’t have a movie). Though the major storylines are all by the book, No Strings Attached gleefully bounds along thanks to the supporting cast. Gerwig, after conquering the indie world with her unique, natural energy, had a breakout year in 2010 with her role in Noah Baumbach’s Greenberg. Here, she provides each of her scenes with a surprising vibrancy, instrumental to the maintaining the film’s casual charm without stopping it dead in its tracks, as so often happens with secondary characters in mainstream comedy. The characters aren't floundering aimlessly in screenplay mechanics, but part of a developed world. (Watch how the crazy producer with a crush on Adam transforms from a one-line joke to an actual character). The awkwardly constructed subplot between Adam, a would-be writer spending his days assisting on a High School Musical knockoff, and his aloof father (Kevin Kline), a famed sitcom actor, comes closest to sinking the film, yet, on the brink of disaster, Kline schmoozes his way through a birthday song, which is funny, yes, but also an exemplary, desperate charade of trying to regain love and respect once it has been lost.

Of course, such charades aren’t needed – something Kline’s ridiculous charicature won’t understand – and, to its credit, No Strings Attached doesn’t solve Adam and Emma’s dilemma with the vapid scenarios that pile up near the film’s conclusion. And while the genre mechanics fall back into all too familiar territory – Emma is the confused one and has to come running back to her [squeaky clean perfect] man, duh – No Strings Attached ends with a nice touch, a punch line, a final reversal of the scenarios it skips at the beginning. For Emma and Adam, it isn’t a question of sex. It’s the problem of breakfast.

Continue reading...

Friday, January 21, 2011

On View: Ben Russell's "Trypps #7 (Badlands)"

by James Hansen

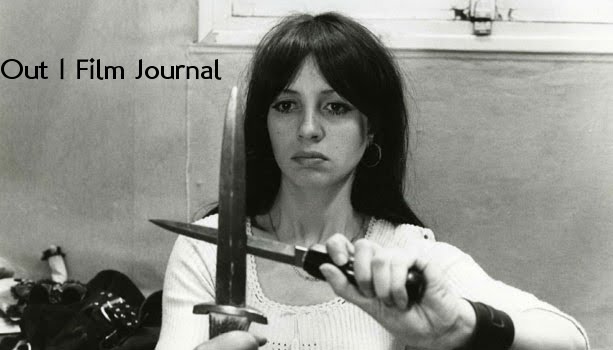

Currently on view at the Wexner Center in The Box (which wonderfully contributes to the work’s critical questions by installing a certain object-to-be-named-later-in-this-”review” along the walls), Ben Russell’s Trypps #7 (Badlands) is all about deception. Drawing on an array of influences and continuing his own engagement with the experiential, trance-like capabilities of moving-image media, Trypps #7 initially appears to be some sort of update on an Andy Warhol Screen Test. A loud bell chimes and a young woman, tripping on LSD, stares out at the camera and the spectator. Shot in Badlands National Park in South Dakota, she stands in front of a barren canyon. She closes her eyes and opens them again. The camera lightly bobs, as if caught in the rustling breeze heard on the soundtrack. The woman’s hair swirls. Another bell chimes, birds chirp, and the wind intensifies. The woman’s eyes seem glossy and her face slides into a smile.

But, suddenly, the film stops and a white light shines out. Another bell. The woman is there again, but the the vivid, blue sky is the only thing behind her. And then, shockingly, the camera swings downward and Trypps #7 spins into the dizzying territory of Michael Snow’s La Region Centrale. (As we will see, this is in no way to suggest Russell’s film is merely a Snow follow up by way of Warhol). When the camera whirls downward and begins to rotate more rapidly, Trypps #7 showcases its initial deception – it is not the camera that is shifting, as in Snow’s film, but rather a double-sided mirror, a reflective apparatus, which, strangely enough, has literally been cracked. We have seen the woman, but only through the representation of a mirror. Between the mirror’s rotations, the actual canyon can almost be seen, but only in the briefest of glimpses. The crack in the mirror indicates our illusion has been broken and the deception uncovered. Yet, Trypps #7 is just getting started.

As the speed of the mirror increases, making perspective and the space nearly indecipherable, the woman leaves the frame, but the mirror continues to spin. Here, Trypps #7 shows our initial “tripping” with the woman has shifted. This is not only a vision of tripping on LSD or merely a film questioning the representative status of the image (not that achieving either of those aims would be any small task). Instead, it becomes a tryppy reflection of the cinematic process actualized. The mirror, ultimately serving as the shutter and douser, rapidly rotates, breaking up our vision, yet a constant stream of different images (enacted by the mirror reflecting in all directions of the somehow unseen camera) flickers before our eyes. Trypps #7 shows us a reflection of a world and a reflection of a reflection of a world. This doubling gives us the opportunity to see an image and understand that the image we see is a deceptive representational reflection of a place we can see, hear, and experience, yet never actually see, hear, or experience in the way that film does. The eye of the camera in Trypps #7 lives inside a projector’s lamphouse, recording and reflecting the process in front of it. Remarkably, Russell puts us in a position to witness the sight of an image passing in front of a stream of light, shattering into small pieces, and uniting as it beams out from a projector.

By embodying multiple positions which are blocked and shifted by the rotating apparatus in front of us (the mirror, the shutter, the douser, etc.), Trypps #7 shows us the full range of what we see when we engage with cinema and highlights the inner workings of the system that we enter into when we experience moving images. Throughout Trypps #7, Russell slowly reveals how he has inverted and coalesced the distinct, divergent processes of Warhol, Snow, and others into a singular, unbounded double or triple-vision which is simultaneously reflective, static, and wildly kinetic. What a trip.

Trypps #7 (Badlands) is on view through January 31.

Continue reading...

Monday, January 10, 2011

January Cages

by James Hansen

In what has become an annual January tradition, movie studios bestow their leftover turds upon various multiplexes and audiences across the country – movies too inconsequential, half-baked, and economically unviable to be gloriously sacrificed among spring comedies, summer blockbusters, fall horrors, and winter “prestige pictures.” January brings with it a super-sized tinge of laziness. (Notably, the same hasn’t been true for foreign film or art houses – two of my favorites of 2010 opened in early January – and many of the Best Movies of 2010 are still working their way to secondary and tertiary markets. Out 1's belated Best of 2010 lists are still in the works. Fashionably late). Alas, the true scent of January is in the air with Dominic Sena’s Nicolas Cage-vehicle Season of the Witch.

So, a long time, there were some witch hunts. And then the Crusades happened. Behmen (Nicolas Cage) and Felson (Ron Perlman) pretty much kicked ass and took names, quipping about single-handedly killing entire armies of men. What a jolly good time! But lo, what treachery is this!? Behmen and Felson are sent into a Church full of infidels, only to realize they are slaughtering women and children. (Cue the repeated smash cut to woman getting stabbed). Pissed at The Church's evil deeds but following their vows to God, Behmen and Felson abandon their army and happen upon a plague stricken town. Discovered to be deserters, Behmen and Felson meet plague stricken Jabba the Hut priest who sends them on a mission from God to take a supposed witch to a faraway town where monks can try her for witchcraft and provide heavenly help to rid their land of the plague.

After collecting a band of hilariously named misfits (a pleasant surprise was Eckhart, played by great Danish actor Ulrich Thomsen), Behmen and Felson wander out into a journey of which they don’t really want to be a part. Neither does the audience. Never quite sure if it’s a sweeping fantasy adventure, an action comedy, or a sci-fi witch thriller, Season of the Witch plods through its running time with constant shifts in tone, a completely transparent plot, and few of the oddly fascinating bursts of unexpected energy typical of Cage. Sena’s blandly dutiful, obligatory storytelling (someone insults witch, witch summons an attack, attack happens, on we go) shreds his actors of their most unique attributes. And despite Sena’s choice to contain the actors and his narrative, Season of the Witch still manages to become resolutely slipshod. With sloppy CGI and non-stop overly descriptive dialogue, mass confusion abounds over what this movie is supposed to be. Sera surely doesn’t know, but he also doesn’t let his actors doing any of the work for him. Instead, Season of the Witch is left to drown in its own ineptitude.

The long-awaited final sequence – a strange riff on Saving Private Ryan with Nicolas Cage being repeatedly stabbed in the back by a demon – provides life support amidst the dreadfully boring slog, but it barely resuscitates it into mild enjoyment. Luckily, shortly after, Season of the Witch ungracefully puts itself down with an overwrought coda (of sorts) among the hills of Calvary dominated by an inexplicable voiceover that is as slack-jawed as it is form fitting. Just because we expect dallying, half-hearted distractions in January doesn’t make them any better.

C-

Continue reading...