by Brandon Colvin

Acclaimed British video artist Steve McQueen’s debut feature film, Hunger, is nothing less than a formal tour de force. Set in the tense political climate of 1981 Northern Ireland, Hunger employs a distinctly partitioned structure to tell the brutal story of IRA leader Bobby Sands’ (Michael Fassbender) famous hunger strike. Sands’ orchestrated protest was enacted to earn Republican prisoners political – instead of merely criminal – status in the face of Margaret Thatcher’s rigid perspective that no crime was justifiably “political,” only criminal. After Sands and nine others starved themselves to death, the IRA was bolstered – Sands was even elected to Parliament in the midst of his strike – but the result of Sands’ actions are not the focus of McQueen’s film. Instead, Hunger is about the moral determination and mental discipline required to turn one’s body into a political weapon; it is a film about process and duration, and, fittingly, it is a film in which the means, rather than the ends, tell the story.

Most broadly, Hunger is a triptych, structured as follows: a nauseating introduction to the harsh prison conditions and fanatical resolve of the Republican prisoners; a lengthy conversation in which Sands explains the necessity of the hunger strike to the discouraging, yet sympathetic, Father Moran (Liam Cunningham); and the somber wasting away of Sands’ starved body. Elegant and direct, McQueen’s film mirrors the martyr narrative of Christ. The film begins with a guard, Raymond Lohan (Stuart Graham) – the guilt-ridden Pontius Pilate – following him to the prison where new prisoners are being interred. A young, non-conforming Republican, Davey Gillen (Brian Milligan), enters into his punishment cell, finding the feces-covered walls, feral faces, emaciated nude bodies, and filthy desperation that Sands, Gerry Campbell (Liam McMahon), and the other protestors live in. As they accept the burden of their cause and assimilate into the protesting prison culture, the prisoners are beaten repeatedly, and forced to run a vicious gauntlet of baton-wielding guards dressed in riot gear. They take lashes and abuse analogous to that of Christ. Their march through the hall of bloodthirsty officers recalls the crucifix-carrying march of Christ to Golgotha. They bear the cross of their sacrifice.

In the film’s middle segment, Sands faces what may be viewed as the last temptation. The film’s centerpiece, a 20-minute conversation between Sands and Father Moran (filmed in two still shots), contains some of the most biting, aggressive, fantastic dialogue in any film. Following the Hunger’s nearly wordless first third and prefacing its equally-dialogue-free concluding segment, this center section is an explosion of thoughts, ideas, and frustrations on both sides of the argument. Father Moran believes the strike may not be necessary, pointlessly destroying the lives of numerous young Irish men. Sands resolutely disagrees and voices his desire for freedom using an eloquent anecdote from his childhood. Nevertheless, Father Moran gives him every opportunity to escape his self-determined fate. Ironically, he plays the role of Satan – tempting Sands to weaken his resolve and forego his role as a potential savior and leader of his movement. Like Christ, Sands does not give in. Following the conversation comes a stunning single shot in real-time of the prison custodian mopping up the urine that the protesting prisoners ritually flood into the long cellblock corridor. Juxtaposed with Sands’ declaration of principles and immediately preceding his isolated starvation, the shot connotes a cleansing effect – a result of his self-destructive action. One cannot help but be reminded of the washing away of sin and damnation brought by Christ’s crucifixion: whereas Christ attempted to spiritually liberate souls, Sands attempts to politically liberate his people.

The film’s final third adopts a light, ethereal palette of hospital whites as Sands enters into his medically supervised final weeks. A sense of purity and asceticism is imbued by the plain, pale tones into every frame depicting Sands’ harrowing starvation. Elliptical and grueling, the film’s protracted culmination shows Sands enduring visits from his family and denying the steady flow of food brought to him, all the while only half-conscious as a result of his physical weakness. This is the slow death on the cross. The clean sheets and applied ointments recall the careful treatment of Christ’s body after death. Once Sands finally shirks off the confines of life, he too is resurrected – his strike being taken up by the next Republican in line, and so on, and so on, resurrected over and over again in the faith of his followers. And while I’m not a religious man, I must say that Sands’ unwavering endurance is the stuff belief is made of. Hunger, then, plays like a ritual, complete with rigorous form, meditative pacing, and repetitious renewal. In his debut film, Steve McQueen has crafted a spiritual, ethical, and political prayer, one of unflinching intensity and striking power.

Continue reading...

Monday, March 30, 2009

McQueen's Martyr

Friday, March 27, 2009

DVD of the Week: "Our Daily Bread" (Nikolaus Geyrhalter, 2005)

by James Hansen

A big apology to everyone for the long delay in posts. I feel like I’m having to say this all the time these days, but I was out of town all last week and hadn’t manage the site particularly well for the week. And, in the meantime, I missed writing a couple reviews I should have written and whatnot. But, onward we trudge! Back up and running at full speed henceforth.

This will start with our DVD pick of the week Nikolaus Geyhrhalter’s 2005 documentary Our Daily Bread. While I anxiously await the arrival of his new film 7915 KM, I have been thinking about Our Daily Bread – a clinically obsessive look at the step by step process of the food industry. The sharp photography collides with the still camera, as Our Daily Bread patiently observes a dedicated, yet oftentimes disturbing process.

But more than being a doc to scare us all off of meat (although, admittedly, I was a vegetarian when I saw it) Geyrhalter’s craft is more what interests me now. Without succumbing to the handheld personal process behind most 21st century documentaries (not that those are all bad), Geyrhalter seems at once classically tuned and radically challenging. Along with Hukkle, Gyorgy Palfi’s amusing 2002 film which would be a fun sort-of companion piece, Our Daily Bread wants the audience to think and feel for itself. Perhaps that is why I have heard many varying reactions to both of the films. More than the content within the film, Our Daily Bread requires a disciplined discourse as part of its process. Although some may disagree, it is a factor that any active audience member should appreciate and, perhaps, adore.

Continue reading...

Tuesday, March 17, 2009

The Curious Case of the "Fanboy"/Critic

By Brandon Colvin

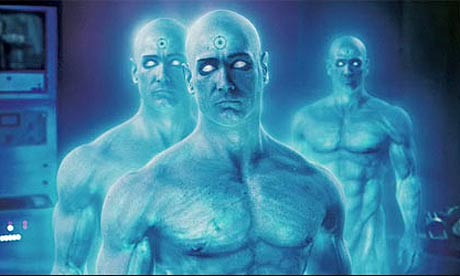

When it comes to Watchmen, it is impossible for me to be an unbiased or even level-headed reviewer. I am, unabashedly, a full-fledged “fanboy” regarding Alan Moore’s 1986 graphic novel. Having read the book over and over, each time feeling more and more slobberknocked by its complex, interlocking structure and carefully crafted plotlines involving the deepest and darkest philosophical and moral conundrums (pretentious but true), I have concluded that Watchmen, the graphic novel, is my favorite non-film narrative . . . ever. (Cue the sneers toward my hyperbole.) As a cinephile, however, much of my appreciation of Watchmen, the graphic novel, comes from my observance of its highly cinematic qualities: movement, angles, juxtaposition, rhythm, visual rhyme, lighting, and framing (not to mention the various cinematic influences on the book’s storytelling from film noir to Dr. Strangelove (1964) to Taxi Driver (1976)). The whole graphic novel is perhaps the closest thing to a movie-on-a-page I have ever experienced, existing in a creative sphere that is just as informed by cinema (if not more) than it is comic books – paradise for a nerd like me who wishes he could sit around and read movies when he isn’t watching them.

Herein lies the predicament of my writing about the cinematic adaptation of Watchmen – I’ve been adapting it for the screen in my head from the very first time I read it. The book was always waiting to be a movie; it only made sense. This, of course, is not true for everyone (as I have been repeatedly informed by the film’s detractors). Therefore, I come to this review as a “fanboy”/film critic in a mild identity crisis. How can I write about this film judging it solely on its cinematic merits when I judged the beloved inked source material, in many ways, based on its cinematic merits? Should I write as if I were not familiar with the graphic novel, like many viewers and reviewers, or should I write as the avid fan that I am? If Watchmen has always existed for me in at least a proto-cinematic realm, how can I express the inevitability and desirability for a filmic adaptation to someone for whom this is not the case? How do I concretely differentiate between a cinematic graphic-novel and a comic-book-like movie?

Okay, okay. This is getting neurotic. You get my point. Extracting my personal investment in Watchmen from my critical perspective is as impossible as it is pointless. I could argue about the validity of its themes, the depth of its characterization, the myriad contradictory conclusions and implications found within its story – all of the elements that can be found in the source material that mean so much to me; however, what I want to attempt to discuss here are the differences between the print and screen versions of Watchmen: what makes the movie more or less successful than the graphic novel and what, if anything, gives it a creative life of its own.

I would insert a plot summary here, but honestly, it would be futile. Summarizing the plot would take up as much space as this entire review . . . it’s pretty intricate. Try Wikipedia – the article on Watchmen is very extensive and thorough.

I’ll begin my assessment of the actual film by responding to a widely-held criticism of the movie – namely, that the Watchmen film is too close of an adaptation of the graphic novel, relinquishing storytelling power via cinematic language in favor of faithfulness to the book’s panel designs and framing. To this, I say, “bollocks.” Watchmen’s (the film) visual storytelling is one of progressive tableau and densely packed framing – certainly in keeping with the methods of the graphic novel, but doing so in a way that is also undeniably cinematic. Why is there a difference in value judgment when describing a film as being “painterly” and describing a film as being like a graphic novel – essentially multiple paintings in juxtaposition? Why is it unacceptable for a film to use the tableau style of comic-book panels to tell a story when those very comic-book panels are, in fact, derivative of previously established cinematic styles? The line seems much too blurry in this instance for me to distinguish what about Watchmen is strictly graphic novel-influenced and what about it is dependent upon filmic traditions. Ultimately, I ask, why does it matter? The techniques of Watchmen undoubtedly add up to a viable cinematic style; I’d say Wes Anderson’s films are just as dependent on artificial, dense framings with relatively little camera movement, much slow motion, and very pictorially expressionistic designs. If The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) were a graphic novel first, would it be undergoing the same criticisms as Watchmen? I think not. Since when is making a formally analogous adaptation a major sin, especially when, in my opinion, it works?

Aside from quarrels with the validity of director Zack Snyder’s quite meticulous adaptation, many complaints regarding the film seem directed at the liberties taken by David Hayter and Alex Tse in their script, which certainly strays from the content of the graphic novel while consistently preserving its brooding, ironic spirit. In order to avoid spoilers for those readers still waiting to see the film, I’ll merely say that both the beginning and end of the film are altered in ways that are very noticeable – rearranged order/continuity and even entirely new plot elements – but, these changes, as well as those throughout the film, are often made in the name of elegance, simplifying some of the more complex and inaccessible aspects of the Watchmen to the point that a theatrical, commercially viable film could be produced. Most “fanboys” seem to have a problem with this; I don’t. It is semi-miraculous that this film even exists and, honestly, I expected it to be a lot worse. Hayter and Tse’s changes introduce new, very interesting dynamics to the plot – including further probing Dr. Manhattan’s (Billy Crudup) potentially cataclysmic role in the alternate reality – and, in many cases, play up the book’s humor. Although some key facets of the graphic novel’s thematic relevance are lost or shuffled, new elements are gained that distinguish the film from its source material; case in point: the soundtrack.

For most fans of the graphic novel I’ve spoken to, the film’s use of chuckle-inducing tunes at the most unusual moments has been off-putting. To me, it reveals that Snyder, Hayter, Tse and the rest of the filmmakers understand the big joke, the ultimate cosmic irony of the whole narrative – the one The Comedian (Jeffrey Dean Morgan) is always talking about and the one that Rorschach (Jackie Earle Haley) claims to understand – deciding to infuse its hilarity into numerous moments throughout the film, the most discussed of which is certainly the now-infamous “Hallelujah” sex scene between Silk Spectre II (Malin Akerman) and Nite Owl II (Patrick Wilson), aboard the latter’s gorgeously rendered flying owl ship, Archie.

A classic case of Watchmen wit, the scene mounts a comical critique of the sexual limitations of its deeply flawed characters, comments on the fetishistic qualities of playing dress-up do-gooder, and implicitly lampoons the super-serious model of superhero stories epitomized by last year’s The Dark Knight – all of which is highlighted by altering/adding to the contents of the graphic novel through the song. In the book, the sex scene is treated quite seriously and the characters’ references to the way wearing their costumes and saving civilians from a fire cures Nite Owl II of his previous impotence is rather straightforward. In the film, the humor of Nite Owl II’s bedroom issues and his dependency on role-playing to get his jollies is amplified by the addition of Leonard Cohen’s song, which coats the scene in a too-serious, too-romantic, trying-too-hard sheen that is as obviously artificial as it is intentionally sarcastic. Using the musical elements unique to the film, Watchmen extracts levels of meaning and presents tonal angles that are somewhat buried in the graphic novel, bringing to light the well-sewn seeds of comedy that line the narrative’s ostensible gravity, while also providing a counterpoint to the total Seriousness that seems to be expected of all comic-book movies in the wake of Christopher Nolan’s somber blockbuster. Which is not to say that Watchmen isn’t a morose film, but at least it seems to understand the value of levity and acknowledges the inherent absurdity of its own fantastical apocalyptic scenario.

Obviously, I’m a bit long-winded regarding this film, which is a fault of my own; Watchmen rattles my brain to the point of discombobulation. To be short, the film is worth seeing. It is worth seeing multiple times. It is different enough from the graphic novel to earn its status as a strong, individual work on its own. If you don’t like the book, however, you probably won’t like the movie. If you haven’t read the book, you should before watching the movie. (Whether that is a flaw in the movie or not, I can’t say. Topping the book is a relatively impossible feat.) The film is by no means a masterpiece, but it is nonetheless impressive in its ambition and execution. There were moments in which I was amazed and others in which I was befuddled, but, as a passionate supporter of the book, I must say I was not disappointed.

Continue reading...

Saturday, March 14, 2009

DVD of the Week: "Tongues Untied" (Marlon Riggs, 1989)

Sorry to everyone for this being a day late. Reviews of Miss March, Last House on the Left, Watchmen, and Hunger are in the works.

by Chuck Williamson

Tongues Untied, the 1989 video collaboration between media artist/queer activist Marlon Riggs and poet/essayist Essex Hemphill, has been burdened for too long by its legacy as a polemical culture war product. When it was first broadcast on public television, the documentary became the target of evangelical moralists and right-wing politicians—particularly Pat Buchanan, who used footage from the video in a presidential campaign ad accusing Bush of funding “pornographic art.” Thus, some might assume that Tongues Untied can only be appreciated as a timely polemic and historical footnote. However, the video defies such criticisms, as it represents both a moving and incisive mediation on the experiences of black gay men and a radical reinvention of the documentary form.

more after the break

As Riggs has stated, “Tongues Untied tries to undo the legacy of silence about Black Gay life.” Foregoing any traditional documentary approach, the video opts for a more experimental method. Blending spoken-word poetry, confessional interviews, and queer performance, Tongues Untied constructs its counter-discourses in response to the reductive, prejudiced view of black gay men, who are doubly-Othered and marginalized within both black and white culture. Through footage of dive bars, voguing balls, snap! performances, pride rallies, and on-the-street interviews, the video documents the cultural happenings of the black gay scene of the late eighties. But the video ultimately moves away from the limiting confines of an objective, journalistic discourse; instead, it fuses fact with fiction, personal testimonial with poetic recitation, on-the-street verite footage with experimental montage. Tongues Untied alternates between interviewed confessionals and prosaic poetry readings, documentary footage and staged homoerotic spectacle. These discursive strategies make the video’s explorations political and personal, thus adding to its urgency and poignancy. In its most powerful sequence, Marlon Riggs delivers a monologue that mixes poetic mediation with pained confession, as he speaks on the intersections of homophobia and racism, and the prejudices that exist within both black and white society. “Silence is my sword,” he says. “It cuts both ways—silence is the deadliest weapon.”

But Riggs’ voice is just one of many. Through the collaging of sound and image, spoken word and visual antecedent, the film transforms silence into a cacophonous roar—and it is a roar that includes many voices. In Tongues Untied, the experiences of black gay men cannot be viewed as singular or monologic, and the video demonstrates this by stitching together its various discourses into a polyphonic tangle that gives the viewer access to a broad spectrum of emotions and experiences.

Out-of-print for over a decade, Tongues Untied has finally been released on DVD by Frameline Pictures.

Continue reading...

Wednesday, March 11, 2009

"Hearts and Minds" Re-Release Trailer

Hearts and Minds, Peter Davis's Oscar wining documentary which explores the various atrocities of the Vietnam War, is being rereleased. The new trailer can be found here. With a new restoration, Hearts and Minds will be well worth (re)visiting not only for its historically emotional resonance, but also for its ever expanding pertinence. It opens in New York on March 20 with a national rollout planned for April. Wherever you are, it is not to be missed.

Continue reading...

Sunday, March 8, 2009

Reviews In Brief: "Birdsong" (Albert Serra, 2009)

by James Hansen

Albert Serra’s Birdsong, a minimalist portrayal of the three wise men’s journey to honor baby Jesus, rests in laurels in textures of lightness and darkness. With only slight references to the scope of their venture, Birdsong remains almost completely void of the extratextual narratological significance of the birth of Christ. Rather, the wise men are portrayed as a trio of bumbling and indecisive fools wandering their way to nowhere. Without choirs of angels singing in exaltation – save the lone music cue of the entire film when they bow uncomfortably bow before Mary, Joseph, and Jesus – Birdsong is quite demanding, but the aimless journey is matched formally by the array of cinematographic choices, most namely the long periods where the frame is filled in almost complete black or white making the wise men oftentimes indecipherable from the textured surfaces and shifting grain. Serra’s formal mastery is never in question, as each shift in color, light, and sound (read: silence) foregrounds a lyrical relationship between the wise men and the audience, both of which become absorbed, oftentimes comedically, in the utter aimlessness and discomfort of the quest. Birdsong requires a deal of patient engagement, but it was impossible, at least for me, to not heed the call.

Continue reading...

Friday, March 6, 2009

DVD of the Week: "Regular Lovers" (Philippe Garrel, 2005)

by James Hansen

Although he has been an important filmmaker in Europe for quite a long time, American audiences are still becoming acquainted with French director Philippe Garrel. And, if you do not live in New York or Los Angeles, it is highly likely that you missed his two most widely distributed features: Regular Lovers (2005) and J'entends plus la guitare (1991, yet distributed for the first time in the US in 2008) which may have been the most devastating film I saw last year. With his latest feature Frontier of Dawn opening in New York this week (expect a review sometime next week), it seems like an appropriate time for everyone to catch up on as much Garrel as possible. Unfortunately, there are still not very many features to choose from (unless you have a region free player). However, that is not to infer that Regular Lovers is not an absolutely extraordinary feature that has already become essential viewing – not only for its thorough and absorbing account of the May 1968 student riots, but also for being, as far as I can tell and from all I have heard, pure Garrel.

(more after the break)

Regular Lovers lingers through its 178 minutes running time – quite a task for some – yet manages moments of crushing clarity and powerful beauty. William Lubtchansky’s luscious cinematography, shot in the highest contrast black-and-white you may ever see, provides a perfect counterpoint to the dreamily troubled ideologies of love and revolution pondered throughout the film’s titular lovers Francois (Louis Garrel) and Lilie (Clotilde Hesme). Although it may have been fixed on the DVD, I recall seeing the film in theaters and the subtitles often disappearing into the bright whites of the landscape. But somehow, rather than become frustrated, every element of the film and its scenario (collaborated on by Garrel, Arlette Langmann, and Marc Cholodenko) continued to flow and slowly reveal itself even without the language spelled out. That is a truly rare cinematic experience. Garrel’s strong directorial command predicates itself on the personal and abundantly heartfelt tone which is fully realized from frame one. Without being annoyingly ostentatious, Regular Lovers is daringly original and seductively transforming.

If you have yet to see any films directed by Garrel (and are a bit adventurous...I know the readers of this site are!), do yourself a favor and check out Regular Lovers. You may be joining the cult of Garrel before you even know it.

Continue reading...

Thursday, March 5, 2009

Short Films You Must See: "Phantoms of Nabua" (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2009)

You can find Apichatpong Weerasethakul's new short Phantoms of Nabua here. I realize this is the second short film entry in a sort period of time, but this one is brand new and calls to be seen. I may try and put together a formal review over the weekend, but I will say that I think this short is rather astonishing. I love pretty much everything Apichatpong does, but this really hits it out of the park. He just keeps getting better, and he's already one of the best directors working today.

And just for an update: sorry about the lack of posts recently. It's that time of year when movies worth reviewing are few and far between. There are plenty of good cinema on the near horizon though, so expect us to get back in the swing of things very soon with reviews of Albert Serra's Birdsong, Jonas Mekas' new work Lithuania and the Collapse of the USSR, Steve McQueen's Hunger, and, of course, Miss March along with many others. We look forward to hearing from you all! Don't be comment shy! We love discourse around here!

Continue reading...